Craig Toocheck has a plan to transform the city of Pittsburgh, while at the same time honoring one of its most famous sons. For over a year, Craig has been conducting a campaign to make the official city song “Won’t You Be My Neighbor” – the theme song from Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Pittsburgh takes great pride in Fred Rogers’ connection to his hometown and Craig imagines a day when “It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood” is sung at all city council meetings and professional sporting events.

Craig has explained his campaign, saying, "The lyrics are inspirational, and the song is an important part of Pittsburgh history and culture… The message that Mister Rogers tried to send is important and could hopefully foster some neighborliness in our city."[i]

Like Craig, I grew up on episodes of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. I get teary listening to his kind, gentle voice, saying “would you be mine, could you be mine, won’t you be my neighbor.” And that anthem seems more important now than maybe ever before. We live in a time when it’s hard to be a neighbor. I, too, am nostalgic for those beautiful days of neighborliness, even if they were idealized even then.

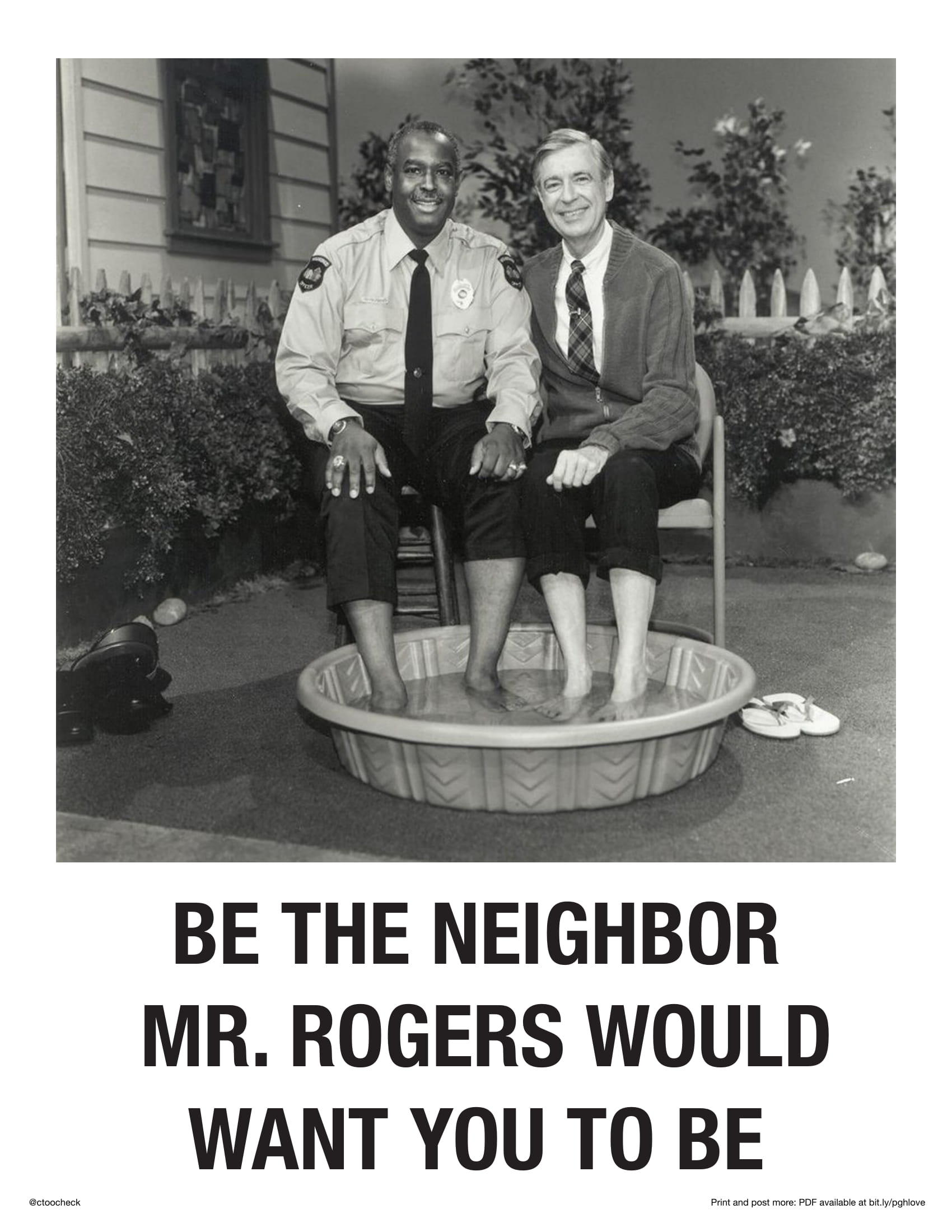

Craig has been hanging posters around town to build support for his cause. One of them reads “Be the Neighbor Mr. Rogers Would Want You to Be.” It’s a message people need to see, in 2018 especially. And I think the message is the modern version of a commandment that appears in this week’s Torah portion, Achrei Mot/Kidoshim: “v’ahavtah le-rei’akha c’mocha – Love your neighbor as yourself.”[ii] It is, perhaps, the most famous of all the commandments in the Torah. And maybe, when you think about it, also the most difficult. It seems so simple, on its face. Just three little words. And yet, the more we stare at them, the more questions they raise. Who is your neighbor? And, how much do you have to love them really? Do you really have to care for their wellbeing as much as you care for your own? And, perhaps most troubling of all, can we even be commanded to love? God can place obligations on our actions, but does God have any jurisdiction over our hearts and our minds?

This is not just a modern quandary. Jews throughout the generations have struggled to understand this commandment – its meaning and its boundaries. This tension is seen in statement of Rabbi Hillel, who lived nearly two thousand years ago, and restated this commandment as “what is hateful to you, do not do to another.” Here, he takes the commandment out of the realm of emotion and reframes it in terms of actions. You must treat others in the way you want to be treated. But to Hillel, how you feel about them is another story altogether.

The tradition acknowledges that your own life and needs will be more valuable to you than the needs of your neighbor. Rabbi Akiva, writing around the same time as Rabbi Hillel, reflects that your life would surely take precedence over your fellow. So how then are we to make sense of “love your neighbor as yourself?” Could it ever really be possible to live this maxim fully, to be as interested in the needs of the other as we are in our own?

There is another version of this commandments, just a few verses later that may shed some light on this challenge: “the stranger who resides with you in your land, you shall not wrong him. [he] shall be to you as one of your citizens you shall love him as yourself for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”[iii] At first this seems even more challenging. Not only are we to love our neighbors, but also the stranger who is residing in our midst. And furthermore, we should see them as being the same as our own citizens. How would that even be possible? But then, we are reminded that we were strangers once too, in the land of Egypt. And suddenly, we are looking at the strangers in our midst differently. We are imagining ourselves in their shoes, and then it is harder to look away. Bible scholar Jacqueline Lapsley explains, “Israel is to remember what being a stranger feels like and is then to ascribe those feelings imaginatively to the stranger. This act of emotional imagination will stir feelings of compassion. Out of this affective response will arise a love for the stranger, which takes form in practical action.”[iv]

I love this phrase “emotional imagination” because this process is rooted in story and creativity. We pass the homeless person on the street and we do not just think of their cardboard sign, or their tattered clothing. We try and imagine the story that lead them to this moment. Are the hardships they have faced anything like the hardships we have faced in our lives? Where do our stories diverge? Thinking this way might change how we see them. We don’t have to be right in our imagining, either, because there is power in the imaginative process. When we put their suffering in conversation with our own, we stretch our heart muscles a little bit. And when those muscles expand, there is a little more room in our heart. And when we are holding space for them in our hearts, we will treat this differently. Empathetic thinking leads to kinder, more loving actions. In this way we stop seeing the people around us as strangers, and start seeing them as rei’akha – as our neighbors. And when we can imagine them with empathy, we can start to love them.

Educational theorist Sir Ken Robinson says that imagination is one of the key elements of being human – the thing that separates us from the rest of the animal kingdom. The ability to creatively imagine someone else’s story is the defining characteristic of our humanity. Perhaps this is what Genesis means when it says that God created human beings “b’tzelem Elohim – in the divine image.”[v] God, the ultimate creator, endowed us with a portion of that creativity. And we can learn to recognize that spark in others, too. When we think of the commandment “v’ahavtah le-rei’akha c’mocha – Love your neighbor as yourself” we tend to get hung up on the complexities of that first word – “v’ahavtah – love.” But maybe we should shift our attention to the last word – c’mocha – as yourself. We know ourselves to be complex beings made up of a myriad of stories. Can we employ our imagination to extend that same honor to other people – to imagine them complexly? Can we picture pieces of our own stories in theirs? And will doing this change how we feel about them? Can we really hate someone, after we have imagined them in this way? Literature scholar Elaine Scarry says that, “the human capacity to injure other people is very great precisely because our capacity to imagine other people is very small.”[vi] Our work, the work of faith, is to try and stretch that imaginative capacity.

This kind of imagining can help us to act with more kindness and more justice. Peter Solovy, a psychologist and president of Yale University has explained that “psychologists… have linked [empathy] to acting ethically and morally. We are more likely to treat other people well if we can find ways to empathize with them. Here, we are told how to act—how not to mistreat strangers—because we can understand their feelings, their hearts.”[vii] Rabbi Emanuel Rackman has called this “empathetic justice” – a moral posture to the world that is rooted in our emotional imagination.[viii]

And boy do we need empathetic justice today! We are living in a world where it is getting harder and harder to imagine our neighbors. Globalization has shattered the barriers between communities. Neighborhoods now transcend ethnic, religious, even national boundaries. Our challenges with what to do about civil discourse, immigration, and conflicts all over the world are rooted in the strength and openness of our heart muscles – in our ability to imagine strangers and our neighbors complexly. Will emotional imagination instantly solve the Israeli/Palestinian conflict or the global refugee crisis? Absolutely not. But what I know is this – we cannot solve these crisis without it.

While it is true that imagination is a divine human gift, it is also true that human beings are not, by our nature great at expanding our definitions of neighbors. Science understands this. Our monkey brains want to be in tribes, want to preserve ourselves and extend our genetic line, but not much more. Jewish tradition understands this, too. Nachmanides writes in the 13th century that we will naturally wish for our neighbor a portion smaller than the one we wish for ourselves. Even our closes friends will come second to our own desires.[ix] But this is exactly why we need this commandment. We are told thirty-six times in the Torah to care for the stranger because we need the reminder. We have to train ourselves to think this way, to exercise our emotional imagination, lest it atrophy. The religious project is to transcend our monkey brains and live generously in complex society – to put our divine creativity to work for humanity.

So maybe Mr. Rogers’ vision of a neighborhood with only beautiful days seems particularly far off at this moment. Maybe the discord between political parties has made us distrustful of our neighbors. Maybe world events trouble us and make us fearful. And fear is the opposite of love. It hardens our hearts. But we know that we are commanded to try and transform that fear back into love. We are commanded to let our hearts open so that they can shape our actions. That poster that Craig Toocheck has been hanging around Pittsburgh, the one with the message “Be the Neighbor Mr. Rogers Would Want You to Be” has an image on it, of two men sitting with their pant legs rolled up and their feet in a kiddy pool. One is Mr Rogers. The other is Officer Clemmons – the black, gay police officer of Mr. Rogers’ neighborhood.

Francois Clemmons, who played the character 30 years, once recounted this experience of coming on this show. "When Fred asked me to play a police officer [I said] 'Fred, are you sure? Do you know what police officers represent in the community where I was raised? And then he started talking about children needing helpers and the positive influence I could have for young children. My heart opened as I listened to him."[x] Clemmons recounted that Rogers was on the front lines of integration. He was one of the first black recurring characters on a children’s television show, and that pool scene from 1969 made big waves in its day (if you will forgive the pun). As Officer Clemmons and Mr. Rogers sat in that integrated pool together, they sang “there are many ways to say I love you.” Today, that image is hanging in posters all over a town where racial tensions are once again on the rise. The goal is to open hearts and minds. The goal is to inspire people to see themselves in their neighbors. The goal is to encourage a new generation to imagine empathetically. Mr. Rogers, in his theme song says, “I have always wanted to have a neighbor just like you, I’ve always wanted to live in a neighborhood with you.” This week’s Torah portion challenges us to look at each person we meet with that kind of radical love. If we did, it might transform the world.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

[i] http://wesa.fm/post/posters-around-city-ask-mayor-make-wont-you-be-my-neighbor-pittsburghs-official-song#stream/0

[ii] Leviticus 19:18

[iii] Leviticus 19:33-34

[iv] Quoted in Held, The Heart of Torah, Vol. 2 (p. 63)

[v] Genesis 5:1

[vi] https://ajws.org/dvar-tzedek/mishpatim-5774/

[vii] https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/97900>

[viii] “Torah Concept of Empathic Justice Can Bring Peace,” The Jewish Week, April 3, 1977: 19

[ix] Quoted in Lebowitz, Studies in Vyikra, (p. 367)

[x] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ObHNWh3F5fQ, quoted here.